Left Anterior Fascicular Block (LAFB)

- Tom Bouthillet

- Aug 18, 2021

- 3 min read

A reader by the name of Jesse contacted me and wrote:

"I have a question. I’m trying to learn more about fascicular and hemi blocks. I was curious if you have posted, or intend to post, any information regarding these. I understand this is all done on your free time, so no rush at all. Any helpful information that you have the time to spare will be greatly appreciated."

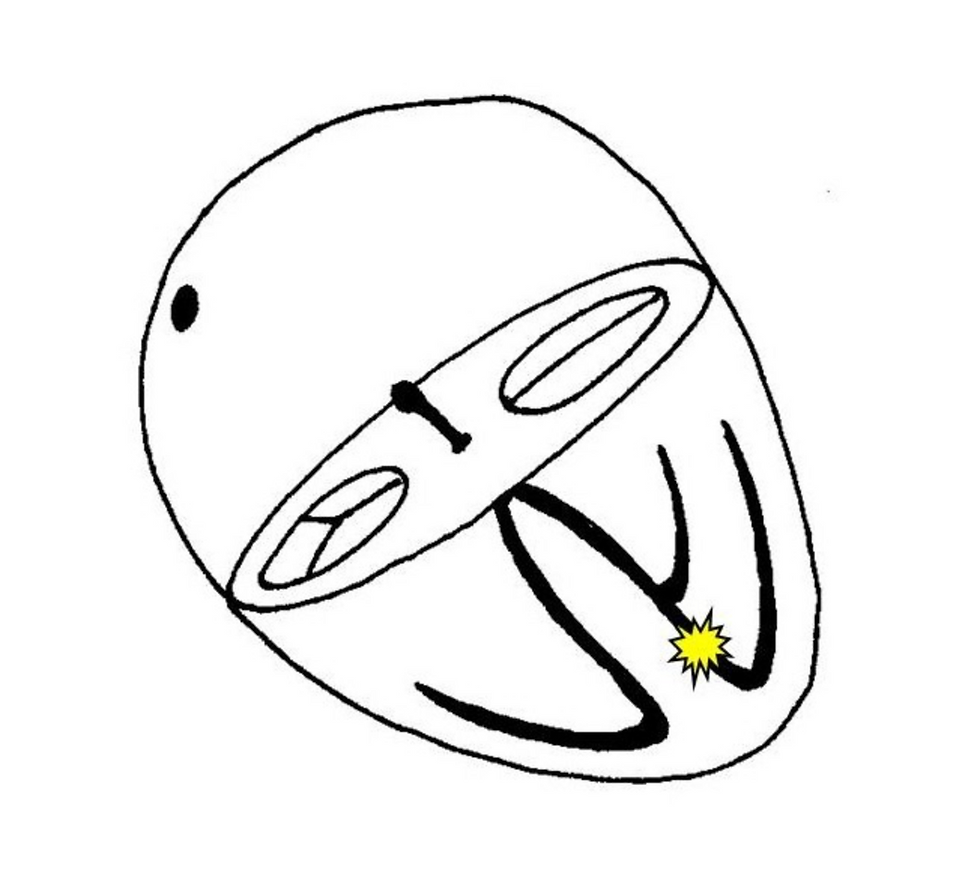

That sounded like a pretty good idea, so I thought I’d start with a left anterior fascicular block (LAFB). But first, we need to answer a more basic question. What is a fascicle? Take a look at this simple diagram of the heart’s electrical conduction system.

Basically what you see here is an outline of the heart. In the center is a schematic of the “cartilaginous ring” or “fibrous skeleton” of the heart. It’s made of collagen (the most abundant protein in nature) and it serves several functions.

It gives structure to the heart and the AV valves in particular, so the heart doesn’t collapse during systole. It’s also electrically inert, so it insulates the ventricles from the atria. The only legitimate electrical connection between the atrial and ventricles is the AV node and AV bundle, which acts as a capacitor, slowing electrical impulses down and then transmitting them to the ventricles. This slowing of the impulse through the AV node corresponds to the PR interval on the surface ECG. That’s important because the delay allows time for ventricular filling. In addition, it prevents sudden death for patients that experience atrial fibrillation. When the atria are fibrillating, what’s to stop the ventricles from fibrillating? The AV node!

That’s exactly why accessory pathways are dangerous, especially in the presence of atrial fibrillation! So, following the AV bundle down you can see that it bifurcates into the right and left bundle branches. The right bundle branch has one fascicle (or branch) and the left bundle branch has two fascicles (or sub-branches). They are called the left anterior fascicle and the left posterior fascicle. The fascicles are part of the heart’s electrical conduction system (the His-Purkinje system). Here’s another diagram I found on the web.

You can see that the fascicles actually fan out into the ventricles to allow coordinated and synchronous ventricular activation. Sometimes, one or more of these fascicles can become “blocked” and fail to conduct electrical impulses. Depending on where the “block” takes place, you can get a RBBB, LBBB, LAFB, LPFB, or bifascicular pattern on the 12-lead ECG. Often the block is the result of heart disease. Sometimes, the block is secondary to an acute process like acute myocardial infarction. In fact, a new bundle branch block is a disturbing finding for a STEMI patient. They derive the highest bene!t from thrombolytic therapy.

Let’s assume for a moment that the left anterior fascicle of the left ventricle is blocked.

What would this look like on the 12-lead ECG? Here are the rules for interpreting a left anterior fascicular block (LAFB).

This is an example of why axis determination is an important part of 12-lead ECG interpretation. The most common causes of left axis deviation are left anterior fascicular block and inferior Q waves secondary to acute myocardial infarction.

Let’s look at an actual example. The following ECGs were captured from a firefighter I used to work with. He had a known history of a left anterior fascicular block (LAFB) which was apparently benign (after lots of expensive testing).

First, the rhythm strip.

Here we have a sinus rhythm with left axis deviation. Now the 12-lead ECG.

Here we can see that the QRS duration is prolonged at 110 ms (but under 120 ms). We also note qR complexes in leads I and aVL and rS complexes in leads II, III and aVF. It doesn’t always look this perfect, but it doesn’t have to. As I’ve said on previous occasions, our patients don’t always read our textbooks!

One last feature I want you to notice is the poor R-wave progression and late transition! This is a normal finding for the left anterior fascicular block (LAFB).

Next time, we’ll address the left posterior fascicular block (LPFB) which is a very rare isolated finding and requires a few caveats!

Comments